During our discussion this week, my group and I focused on determining what narrative parallels we could establish between components of the Book of Exodus and myths of other religious traditions, as well as what the concept of martyrdom meant to each of us personally.

Parallels with Exodus

For our discussion on narrative parallels that existed between the Book of Exodus and myths in other religions, we did not just focus on discussing two components from the Book of Exodus, instead we each chose two different parts of the myth to explore and compare, some of which I will make note of here. Furthermore, our discussion on the narrative parallels can be divided into discussions over the parallels in narrative elements and parallels in narrative themes.

Narrative Elements

Component 1 and Parallel

For the discussion on narrative elements within the Book of Exodus which could be paralleled with myths from other religions, the component of Exodus which we focused upon was Exodus 1-2:10, the entirety of the first chapter and the first half of the second chapter. To summarize, Exodus 1 describes how the Egyptian Pharaoh, in the time period of Moses’ birth, perceiving the Hebrew people in Egypt as a potential threat if war breaks out, chooses to enslave them and oppress them. As part of this threat reduction strategy, he also orders his people and the Hebrews to kill any Hebrew baby boy as soon as they are born by casting them into the Nile. Exodus 2:1-10 focuses on the birth of Moses and how his mother, in an attempt to protect Moses, places him in a basket and hides him on the Nile River wherein he is discovered by the Pharaoh’s daughter, who pitying him ultimately protects him by taking him as her son.

Israel in Egypt

(Poynter, 1867)

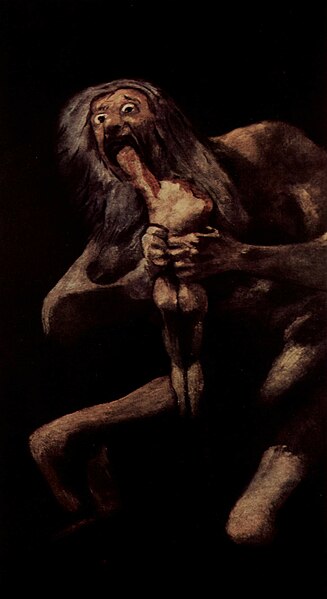

A myth with common narrative elements to the beginning sections of the Book of Exodus was the Greek myth concerning the birth of Zeus. At the time of Zeus birth, his father Cronus, fearing that one of his offspring would kill him and usurp him, chooses to devour them as soon as they are born, an act which he does to all of Zeus’ siblings, so as to kill them and remove them as threats to his reign (although they survive and become captives within his body, effectively “oppressing” them). Zeus’ mother, the Titaness Rhea, desiring to save her last child, Zeus, deceives Cronus by feeding him a stone and having Zeus spirited away to be raised hidden under the protection of another deity, Gaea, or mother earth in Greek mythology.

Saturn [Cronus] Devouring his Son

(Goya, 1819-1823)

In both narratives, the destined saviour of their respective brothers and sisters (Moses and the Israelites; Zeus and the Olympian Gods) is born into circumstances wherein a ruling figure (the Pharaoh and Cronus) attempts to oppress and kill the saviour’s people (the Hebrews/Israelites and the Olympian Gods) whom are perceived as threats to the ruling figure’s reign. Another clear parallel can be seen in how Zeus and Moses both needed to be hidden away by their mother from the threat to their newborn existence, before being raised under the protection afforded to them by a secondary mother figure (the Pharaoh’s Daughter and Gaea). It is also interesting to note how both the secondary mother figures share a familial relationship with the oppressor in both myths (Gaea is Cronus’ mother, whereas the Pharaoh’s daughter is very obviously the Pharaoh’s daughter).

Component 2 and Parallel

The second component of the Book of Exodus, wherein there are narrative elements which can be paralleled with myths of other religions is Exodus 19-23. To summarize this section of the Book of Exodus, this part of the narrative takes place in the aftermath of the Israelite’s liberation and migration from Egypt, a time when they are no longer living lives of oppression under the Egyptians. During this time, Moses goes atop Mount Sinai where the Israelites’ God speaks to him, telling him of the laws and customs which the Israelites must follow, lest they incur the wrath of God. Among these laws are the Ten Commandments, a fundamental cornerstone of Judaism (and all its associated religions). Furthermore, God also outlines where the Israelites will settle, the so-called “Promised Land.”

“I will establish your borders from the Red Sea[a] to the Mediterranean Sea, and from the desert to the Euphrates River. I will give into your hands the people who live in the land, and you will drive them out before you.” (Exodus, 23:31)

The myth that we felt paralleled this part of the Book of Exodus is the Hopi Origin story which was covered in the second week of class. Within the Hopi origin story, the Hopi, having only just emerged from an existence below the earth, encounters the caretaker of the earth, Maasaw, who teaches the the Hopi to honour mother earth and take care of her, as well as instructs them to settle in the “center place.”

Within both stories, there are many elements which we can see are parallel to one another. The peoples with which the stories are centered around respectively have both only recently (in the context of the myth) entered into a new existence: the Hebrews/ Israelites are no longer oppressed Egyptian slaves while the Hopi have ascended from below the earth. Both peoples are enlightened by a deity to what will become a cornerstone belief in their respective religions: God teaches the Israelites the Ten Commandments through speaking with Moses; Maasaw teaches the Hopi to honour mother earth and take care of her). Finally within both narratives, the deity also tells their respective peoples where they are destined to settle (God describes to Moses where the Israelite “Promised Land” is situated; Maasaw tells the Hopi to settle in the “center place”).

Narrative Themes

Component 1 and Parallel

For narrative themes, our group discussion focused upon messages which we could derive from the Book of Exodus which could be applied broadly to other narratives in other religions. The first theme that we found was the idea God is merciful. The component of the Exodus myth that we focused upon here were the plagues featured in Exodus 7-10, the plagues of: Blood, Gnats, Flies, on Livestock, Boils, Hail, Locusts, Darkness. In each of these plagues, the Israelite God caused great calamities to occur in Egypt for the Pharaoh’s continued refusal to free the enslaved Hebrews but relented each time when the Pharaoh promised Moses that he would give them their freedom. Ultimately this action, as one group member pointed out demonstrated how God, through the plagues, was still giving the Pharaoh a chance to rethink his actions and ask for God’s forgiveness, demonstrating the merciful nature of God. Furthermore, this group member also noted how this is reflected in the description of the Israelites’ God in the Quran as Allah the most Merciful.

Component 2 and Parallel

The second narrative myth we drew from the narrative of Exodus was the idea that only God should be feared. The component of Exodus which we drew this from was Exodus 32, the passage wherein the Israelites turn from God and worship an idol of a Golden Calf. As punishment for this sin, God says to Moses:

“Whoever has sinned against me I will blot out of my book. Now go, lead the people to the place I spoke of, and my angel will go before you. However, when the time comes for me to punish, I will punish them for their sin.” (Exodus, 32:33-34)

While the book of Exodus does not tell us what this punishment is, the Book of Numbers describes how the Israelites, in their initial efforts to scout the “Promised Land” finds their entry to their destined area of settlement barred by giants, which ultimately causes the Israelites to realize that they are being punished for their act of idolatry, thus teaching them to fear God alone. Our group member once again pointed out how this theme is reflected throughout passages in the Quran, wherein it is explained that there should be no other fear except for Allah.

As an extension of this second narrative theme, our group expanded upon this idea of fearing a deity by comparing the Israelites’ punishment for their idolatry in Exodus with the divine punishment encountered by the Greeks for their actions in the immediate aftermath of the Trojan War. After the defeat of Troy, many of the Greek heroes committed many atrocities during the sacking of the city, one such example of these atrocities which we discussed was the rape of Cassandra, by the Greek hero Ajax the Lesser within Athena’s own temple, wherein Cassandra had been clutching a statue of Athena in supplication to protect herself. This act, and many others like it (an example being how the Trojan King Priam is murdered by the Greeks on an Altar of Zeus) go unpunished, ultimately leading to the Olympian Gods wrecking the Greek fleet on their return voyage from Troy and the deaths of many of the Greek warriors, including Ajax the Lesser, for these sins. While it is not a sin of idolatry like in the Exodus narrative, we felt that this was a parallel to the message of fearing a deity as this myth surrounding the destruction of the Greeks as a result of their atrocities in Troy demonstrates how the Greeks were instructed to be mindful of their conduct and their actions lest they incur the wrath of their gods, similar to how the Israelites learned to fear god through their punishment for the Golden Calf.

Perspectives on Martyrdom

The second part of our group’s discussion delved into our own perspectives on the concept of martyrdom. As this was an optional part of our discussion, there was only a limited degree of engagement on this sensitive topic.

*My Personal Take on the Question

My perspective on the situation, which I also included in the discussion, as someone who comes from a Christian, albeit Catholic, background is that martyrdom is an act which exemplifies faith or belief in any given religion. My perspective is primarily drawn from my observation of Christian saints, many of whom were canonized within the Catholic church due to their suffering as martyrs, whom even unto the pain of death, refused to forego their belief in God and the Catholic promise of life after death with God, despite the fact that they could have easily spared themselves the suffering or saved themselves from untimely death if they had done so. Martyrdom reveals the capability of individuals to hold on to faith even in the most dire of circumstances, and in my opinion, provides an ideal for faith that believers of any religious background should aim for, though one that they need not replicate.

Group Discussion

Another group member noted that martyrdom played a large role in their religion. They believed that the idea of Martyrdom stemmed from Christ’s death and resurrection, the most fundamental part of beliefs across all Christian denominations. Martyrdom, in their opinion, emulated the holiest act Christians know of, the sacrifice of Christ, as it symbolized sacrificing one’s life for one’s beliefs. They also noted that they were taught that martyrs are guaranteed a place in heaven and can even be declared as saints of the church depending on the good deeds they committed for the poor. As an example of this, they referred to an incident on in December 1991, wherein 144 Ethiopian Christians were killed for wearing a cross around their neck. In the present day, they have all been declared as martyrs and the Ethiopian Orthodox church recognizes the day of the tragedy, commemorating it through the act of charity by giving food to the poor. This group member stated that martyrdom was ultimately an act representing strong faith and principle, which ultimately meant that martyrdom could be applied beyond a religious context.

This group member’s discussion on the fact that martyrdom need not remain in the realm of religion opened up our discussion to other applications of the concept of martyrdom, such as politics. This allowed our discussion to touch upon martyrdom as it has appeared in relatively recent news. We noted in our discussion how martyrdom could, contrary to both my perspective and that of my group member’s, exist separately from faith, and that not all martyrs were individuals who died for a cause, rather they could be individuals who died to become a cause.

Examples of Martyrdom (Non-religious) from the News

As an example of an individual who was martyred, outside of the scope of religion, to become or inspire a cause, we can analyze the death of Mohammed Bouazizi. Mohammed Bouazizi, was a Tunisian street vendor, who as a result of harassment from corrupt police officers and market inspectors, as well as his inability to have his grievances heard by authorities, committed an act of self-immolation to protest the treatment he had received, later dying in early 2011 from the injuries he received (The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2020). His death came to symbolize many of the struggles faced by individuals in the middle east and ultimately it was what inspired the various protests and uprisings of what we now know as the ‘Arab Spring,’ effectively making him a martyr for the movement, though he did not die for his belief in the movement, but rather because his death became the cause of the movement.

Another, even more recent example of this form of political martyrdom would be the death of George Floyd. According to an article by the BBC (2020), George Floyd, as many of us may know, was an African-American male whom on May 25th, 2020 was killed during an arrest by a police officer kneeling on his neck while he was on the ground. His death, like the death of so many other African-Americans became a symbol of the senseless police brutality, marginalization, and discrimination faced by Black people, not just in America, but across many countries globally. Furthermore, his death sparked protests both internationally and within America concerning police brutality as well as racism against Black minorities. Once again, we see the example of a martyr whom did not die for their faith or beliefs, but achieved martyrdom because he and the circumstances surrounding his death resonated with so many others that he, in effect, became a cause for others to rally around.

Real-Life Religious Martyr Example

An example of a modern religious martyr would be Father Ragheed Ganni, an Iraqi priest who was killed alongside three other deacons in 2007, by Islamist fighters after they all refused to convert to Islam (Pentin, 2018). In this example, we see the example of a martyr who does die for their faith, as even when he is threatened by the armed men to convert to Islam, Father Ragheed Ganni refused to do so, holding on to his faith in God even though such an act doomed him to death.

References

BBC. (2020, July 16). George Floyd: What happened in the final moments of his life. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52861726.

Bible Gateway passage: Exodus 23 – New International Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus+23.

Bible Gateway passage: Exodus 32 – New International Version. Bible Gateway. https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Exodus+32.

Goya, F. (1819-1823). Saturn Devouring His Son [Oil on canvas]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saturno_devorando_a_sus_hijos_por_Goya.jpg.

Pentin, E. (2018, May 15). Father Ragheed Ganni’s Cause for Canonization Officially Opened. National Catholic Register. https://www.ncregister.com/blog/edward-pentin/father-ragheed-gannis-cause-for-canonization-officially-opened.

Poynter, E. (1867) Israel in Egypt [Painting]. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1867_Edward_Poynter_-_Israel_in_Egypt.jpg

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2020, March 25). Mohamed Bouazizi. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mohamed-Bouazizi.

RELS 200, D2L Discussion III

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.